Whales are some of the planet’s most iconic marine animals and are found in all oceans. They are part of the Cetacea group of marine mammals which also includes dolphins and porpoises and the largest animal in the world; the blue whale.

While often thought of as strictly cold water animals, many whales migrate to the equator to breed. Several whale species migrate north from the Southern Ocean into the warmer waters of Australia to breed during the winter months.

Some whale populations along the Australian coast (and around the globe) were dramatically reduced during historic commercial whaling activities. As a result, several whale species are now listed as threatened in Australia under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act. All cetaceans are now protected in Australian waters.

Despite current protection, whales continue to face threats in Australian waters including entanglement in marine debris and fishing gear, collisions with ships, ingestion of rubbish and environmental change (e.g. melting sea ice in polar regions) as a result of a changing climate.

Our research

AIMS research focusses on the vulnerable humpback whale and the endangered pygmy blue whale populations in Australia’s north west.

Pygmy blue whales

Many people know blue whales are the largest animals on the planet. But you may not know there are several species of blue whale. Pygmy blue whales are the smallest at approximately 24 metres in length, which is only a few metres shorter than the largest; the Antarctic blue whale (up to 30 m).

Pygmy blue whales have small populations partly because they are still recovering from the whaling era. They spend much of their life far from land, below the waves, only surfacing for short periods to breathe. This makes them difficult to study.

AIMS have been researching this elusive and endangered giant since 2019 in collaboration with the Centre for Whale Research (CWR). Our teams are revealing the distribution (the area they use and the most important areas) and the migration and feeding behaviours of pygmy blue whales, with a focus in Australia’s northwest – a region lacking information, but where industrial activities such as mining, shipping and fishing pose potential threats.

Our research is helping decision makers understand the threats posed by human activities, to support pygmy blue whale conservation and their eventual recovery.

Where do they go, and what do they do?

To learn more about pygmy blue whale behaviour during their migratory movements between Australia and Indonesia, AIMS and collaborators CWR and Curtin University tagged whales with satellite transmitters at North-West Cape and Perth Canyon. The team also used noise loggers (underwater hydrophones mounted on the sea floor and on gliders) to listen for and record whale calls.

The data was combined to model and map the area pygmy blue whales use, and define areas of significance such as where they spend the most time, where they are likely feeding, and where these areas overlap with human activities.

This research was part of the North West Shoals to Shore Research Program (NWSSRP).

Learn more:Pygmy blue whale movement, distribution and important areas in the Eastern Indian Ocean

Studying how giants eat on the run

Since 2021, the pygmy blue whale research team has focussed on where the whales search for food and feed. Food fuels the whales’ migration and breeding activities – both key to the species’ recovery. This research is conducted in partnership with Woodside Energy.

In addition to satellite tags, the team use satellite-linked dive loggers attached to the whales to discover the whale’s movement behaviour beneath the waves.

The two different tag types collect a wealth of information on the whales.

Satellite tags track the position of the whales each time they come to the surface to breathe. This allows scientists to follow the individual whales in almost real-time along their migration route to Indonesia.

Dive loggers, on the other hand, provide information on the whale’s activities below the surface, such as the depth whales dive to find their prey (usually krill). Just like wearables for humans, the tags constantly record time, depth, temperature, speed and body orientation. Analysis of this data helps the scientists ‘see’ what the whale is doing.

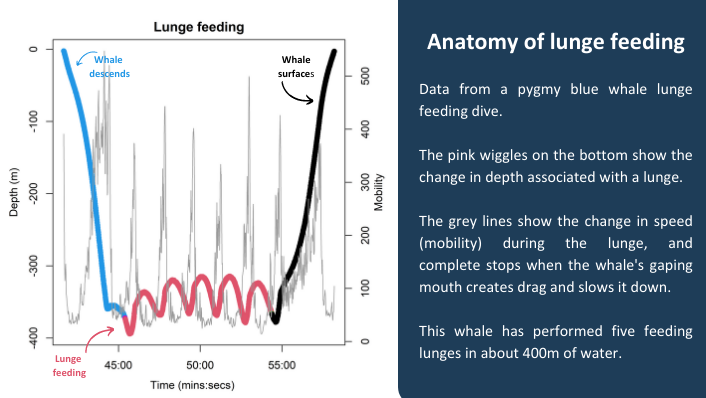

For example, during so called “lunge feeding”, pygmy blue whales speed up to catch schools of krill. As they open their huge mouths to engulf the prey, they come to a complete stop. This signature pattern of speed and body orientation can be clearly identified in the data record.

Pygmy blue whales are deep divers. These loggers have recorded dives to 498 m in the Perth Canyon.

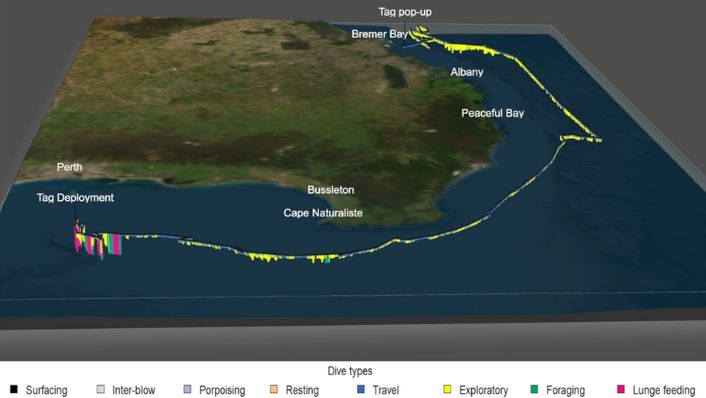

AIMS has recently produced 3D maps (below) showing where foraging and lunge feeding (as well as other behaviours) occur along the pygmy blue whale migration route. These maps, combined with the previous distribution maps produced can be used by governments and industry to better understand the overlap between whale feeding areas and human activity, reduce potential threats to the whales and better manage their important habitats.

Humpback whales

AIMS' humpback whale research was conducted as part of the Western Australian Marine Science Institute’s (WAMSI) Kimberley Marine Research program.

The research involved studying humpback whale distribution and movements in the region, identifying important areas and habitats such as calving and nursing areas. Understanding where whale activity and human activities overlap allows us to identify these areas as high risk. Such information helps focus management and conservation efforts for the region.

Despite their large size, monitoring humpback whale populations is difficult and costly given that they often occupy vast, remote areas. This is particularly true along sparsely populated coastlines such as Australia’s north west.

Computer recognition of whales in high resolution satellite photos of the area was developed as a novel technique as part of this research. This is an efficient way to help the Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife monitor breeding humpback whales in the Lalang-garram/Camden Sound Marine Park.