Quick summary

-

Coral bleaching is a coral’s response to stressful conditions. During bleaching, a coral will expel tiny algae from its tissues turning it white. It is not dead, but very stressed. It may die if the conditions are prolonged or extreme.

-

Bleaching is often brought on by heat stress. Changes in salinity, light, cold water and other stress can also cause corals to bleach.

-

Ocean temperatures are warming due to climate change. This is causing coral bleaching to occur across larger areas more frequently and more intensely.

-

AIMS scientists work with partners to monitor and understand coral bleaching. We are global leaders in reef adaptation and restoration science, collaborating with others to develop ways to help coral reefs survive climate change.

A powerful partnership between coral and microscopic algae

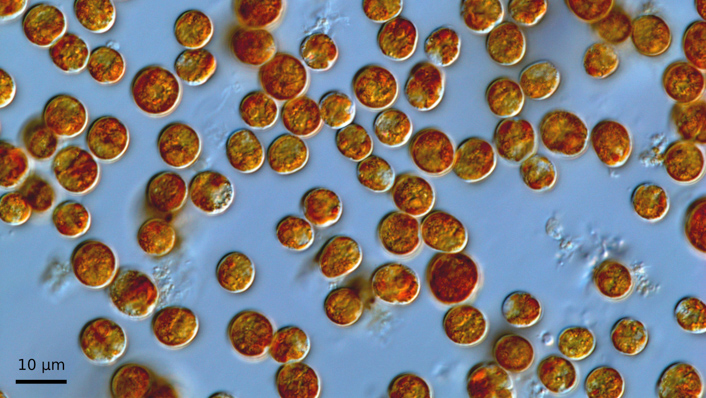

Corals appear to be simple animals that live in colonies; however, they have complex relationships with microbes. Of particular importance are zooxanthellae (pronounced zoo-zan-thel-ay). These are tiny (micro) algae which live inside a coral’s clear tissue. Known as Symbiodiniaceae (pronounced sim-bi-oh-din-ay-see-ay) by scientists, these microalgae receive protection and essential nutrients from their coral host and give them their colour.

In return, the algae feed corals with sugars produced from photosynthesis. More than 90% of corals’ food requirements come from this solar-powered energy source. This helps them build their calcium carbonate, or limestone, skeletons.

This mutually beneficial relationship between corals and their tiny algae is a form of symbiosis. It is the reason corals can build an extraordinary variety of growth forms, providing homes to countless other reef animals and plants.

When relationships go bad – the coral bleaching process

Corals are sensitive to unusual conditions such as warm or cool water temperatures, low salinity, and pollution. In the case of stressful temperatures, the algal symbiont becomes toxic to the coral animal. The coral animal responds by expelling the symbiotic partner from its tissues as a survival strategy during the heatwave.

As the algal symbiont leaves the coral, the coral’s thin tissue becomes transparent, revealing its white skeleton underneath. The typically ‘dark brown’ colony becomes pale as the coral ‘bleaches’.

Not all bleached corals are white. Some severely stressed corals become bright pink, yellow or blue while they are bleaching. These colours are fluorescent pigments made by the coral as a sunscreen to help protect against ultraviolet light. While these corals may appear beautiful, they are stressed and trying to survive.

Bleaching affects corals in different ways

Bleaching is not always a death sentence for corals. Some corals die, but others can recover, depending on how hot and stressful the water gets, and how long the high temperature persists.

Some large corals may show different levels of bleaching across the colony. For example, parts exposed to more sunlight may severely bleach and die, while shaded parts of the same colony will escape intense bleaching and remain relatively unaffected or recover.

Corals which recover may suffer in other ways. They may grow more slowly, have reduced capacity to reproduce, or be susceptible to disease for several years after bleaching.

Some coral species bleach more easily than others. Historically, fast-growing branching corals (for example, Acropora species) are more likely to bleach than slow-growing massive species (like Porites species).

Sometimes, there are even differences between corals of the same species growing side by side – one bleaches, and the other does not. AIMS scientists are investigating the reasons for these differences to help guide future restoration efforts.

Mass coral bleaching - climate change and marine heatwaves

Corals are adapted to warm tropical waters but live within a narrow temperature range. Temperatures that are 1-2oC above the normal summer maximum for only a few weeks can create heat stress and cause them to bleach.

Marine heatwaves are periods of unusually warm water and can cause widespread coral bleaching through heat stress. Marine heatwaves are now more frequent, more widespread, more intense, and longer-lasting due to climate change.

Widespread coral bleaching on a regional scale is called mass coral bleaching.

Today's mass bleaching events are a modern phenomenon. There are no historic records of large-scale coral bleaching at the scale and severity we are now seeing. There is no evidence of large-scale bleaching events in the Great Barrier Reef’s 500-year coral core history.

The first reports of mass coral bleaching emerged in 1983 in the eastern equatorial Pacific.

Until the late 1990s, coral bleaching mostly happened locally, affecting only small, isolated parts of reefs. These events tended to occur because of freshwater runoff after storms, or extreme low tides.

When corals bleach, the reef suffers

Bleaching does not just affect corals. The impacts affect many reef animals because corals form the complex habitats that marine animals need. Fish, for example, typically decrease in numbers after a bleaching event. Even species that do not feed directly on corals suffer, because they need diverse complex reef structure for places to hide.

As a result, a coral bleaching event can dramatically change the make-up of a coral reef in the short- and long-term.

If many corals die as a result of severe bleaching, a structurally complex reef (one with many holes, nooks and crannies which provide food and shelter) becomes flatter and less diverse as susceptible species are lost, and only heat-tolerant and resilient survivors remain.

Corals are not the only animals which bleach – anemones and clams also bleach when stressed.

Recovery from mass coral bleaching

A bleached reef is not a dead reef. Live coral can return after bleaching events, just as it does after other disturbances such as cyclones. A diverse reef community can re-establish if given enough time without another large disturbance. This may take 10-15 years to establish.

But climate change is causing more frequent, extensive, intense, and longer-lasting marine heatwaves. This, combined with other pressures, gives reefs less time to recover.

Warmer oceans and climate change - a threat to reefs worldwide

Large-scale bleaching events are the greatest threat to the world’s coral reefs. As our climate heats in response to human activities, tropical oceans are now hotter than they used to be. As a result, widespread mass bleaching events occur more often. For example, the Great Barrier Reef suffered four mass bleaching events between 2016 and 2022.

Since the late 1990s, mass coral bleaching events have caused significant loss of coral cover, including on the Great Barrier Reef and some reefs in Western Australia. The Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network found the 1998 global event alone killed approximately 8% of the world’s corals.

The future of coral reefs requires reduction in global greenhouse gas emissions, to stabilise temperatures, management of local pressures, and the development of interventions to help reefs adapt to and recover from the effects of climate change.

Science for solutions and management

From understanding the history of coral bleaching, to developing large-scale solutions to boost coral resilience and recovery, AIMS’ research is at the forefront of coral bleaching science:

-

providing real-time oceanographic data to science and management communities to understand marine heatwaves and predict bleaching

-

documenting coral bleaching through routine monitoring and collaborative aerial surveys

-

investigating the genetic make-up of corals and their symbionts to understand corals’ ability to adapt and acclimatise to warming oceans

-

assessing both fine-scale and reef-scale outcomes for corals and other reef animals

-

documenting bleaching histories through the largest coral core library in the southern hemisphere

-

developing actions and interventions that can restore and help reefs adapt to a warming future.