New research is helping to unlock the connections between corals and the dispersal patterns of their offspring, which is critical for predicting their ability to adapt to climate change.

Scientists from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) and the University of Queensland (UQ) have for the first time quantified the distances coral larvae from two species disperse, finding stark differences in their abilities to spread to new areas and maintain genetic diversity.

Lead author on the research, Zoe Meziere, a PhD student at UQ and AIMS said: “Well connected corals that disperse widely have a better chance of adapting to climate change and other environmental pressures.

“Species that don’t disperse as far are more likely to form isolated populations, reducing their capacity to recover from bleaching events or habitat degradation.”

The study examined two coral species with different reproductive strategies, finding stark differences in their ability to disperse and maintain genetic diversity.

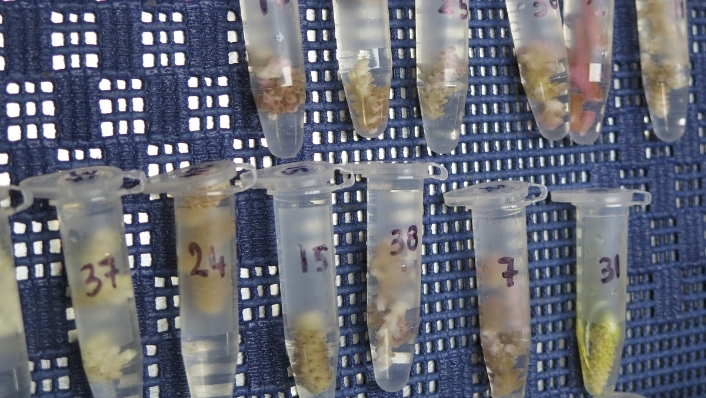

Stylophora pistillata, a brooding coral species where eggs are fertilised in the mother coral, was found to disperse over very short distances — just a few metres. Larvae of the broadcast-spawning species Pocillopora verrucosa – which releases masses of egg and sperm bundles which float away and fertilise in the water column - could travel across tens of kilometres.

Over evolutionary timescales, these differences have profound impacts. S. pistillata populations were more genetically distinctive, with much lower genetic diversity and smaller population sizes than the more widely dispersing P. verrucosa.

Dispersing further and sharing genetic variation with reefs nearby gives corals like P. verrucosa a better chance of rebuilding its population size after natural disaster

Professor Cynthia Riginos, senior author of the study from AIMS and UQ, said this helped to explain why some coral species are more vulnerable to local extinctions.

“Species that don’t disperse far are more likely to form isolated populations, reducing their capacity to recover from bleaching events or habitat degradation,” she said.

The findings highlight the need for conservation and reef restoration efforts to account for the natural patterns of connectivity among coral populations.

“Restoration efforts should focus on species that have naturally limited dispersal, as this could boost their genetic diversity and improve their resilience across the entire reef system.”

“We have a narrow window of opportunity to build reef resilience through reef restoration and adaptation solutions. This breakthrough in knowledge of how far baby corals travel before they settle on the Reef will support reef conservation in the face of climate change impacts”, said Mia Hoogenboom, Acting Executive Director of the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program.

A paper on the research has been published in the journal Science Advances.

This research was supported by the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program (RRAP) and conducted in collaboration with partners at AIMS and James Cook University. RRAP is funded by the partnership between the Australian Government’s Reef Trust and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation.