Research published today in Nature rigorously documents the 2016 mass bleaching on reefs of Australia’s west and east coasts and confirms the link with unusually warm water temperatures. AIMS scientists were part of a multi-institutional team who co-ordinated their efforts to undertake extensive aerial and underwater surveys of bleaching occurrence and intensity along the Great Barrier Reef and Western Australian reefs in early 2016. The unusually warm water temperatures were a result of the exceptionally strong 2015-2016 El Niño, compounded by increasing baseline temperatures due to global warming.

A diver monitoring coral bleaching on the central Great Barrier Reef during the 2016 mass bleaching event. The event was due to high ocean temperatures caused by both a strong El Nino, and increasing baseline temperatures due to global warming.

AIMS’ capacity to undertake long-term assessments of reef conditions, past disturbances and recovery periods helps place this recent event in context. Mass coral bleaching occurred previously on the Great Barrier Reef in 1998 and 2002 when 45% and 42% of the reef escaped bleaching, respectively. During these past events, extreme levels of bleaching were only observed on about 10% of the reefs.

However, in 2016 the proportion of reefs experiencing extreme bleaching (defined as more than 60% of the corals within an individual reef bleaching) was over four times higher compared to 1998 or 2002. This demonstrates that both the geographic footprint and severity of bleaching is expanding. Bleaching was most severe in the northernmost 1,000 km of the reef where virtually every coral species were affected, including massive colonies that are centuries old. Bleaching was less severe in the central and southern parts of the reef where surface water temperatures were fortuitously cooled by local weather conditions.

Off the west coast, bleaching was most severe near the Kimberley coast, Christmas Island and Scott and Seringapatam reefs. Thermal stress at more southerly reefs was reduced due to a tropical cyclone and ocean currents. Scott Reef also extensively bleached in 1998 but AIMS scientists previously documented (Gilmour et al 2013) remarkable recovery within 12 years of all but the oldest corals on this isolated reef system. The new study shows, however, that previous exposure to bleaching stress does not lessen the impact of subsequent events.

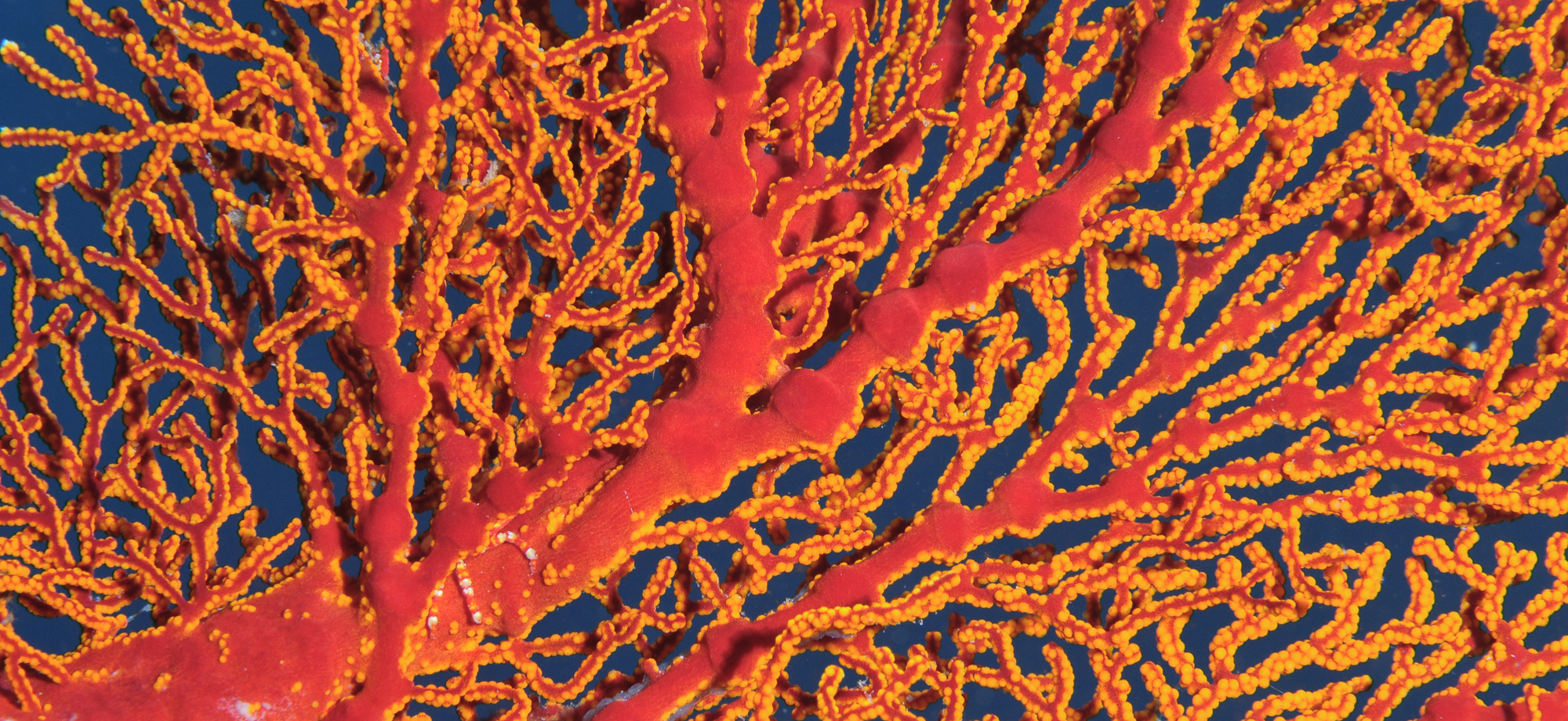

Scott Reef, amongst other reefs off the coast of Western Australia, suffered severe bleaching in 2016. The remote reef had experienced mass bleaching in 1998 prior to this event.

Reef protection measures, such as green zones with no fishing and low levels of local human impacts, did not provide reefs in the northern GBR with protection from the high level of thermal stress in 2016. As the oceans continue to warm, coral bleaching will become more frequent and reefs will have less time to recover between these disturbances. This will result in dramatic changes in the makeup of coral reef communities. Indeed, more bleaching is currently occurring on the Great Barrier Reef.

The AIMS Long-Term Monitoring Program and other targeted research activities will seek to document the full extent of the impacts of the bleaching event in the years to come, to support the development of actions that will promote the recovery potential along the length of the Great Barrier Reef.

The paper “Global warming and recurrent bleaching of corals” by T.P. Hughes et al is available online today.

For media enquiries:

Mr Steve Clarke -Communication Manager

Tel: +61 (7) 4753 4264 (AEST, GMT+10 hrs)

Mob: +61 (0) 419 668 497

s.clarke@aims.gov.au