A crucial tool in large scale coral reef restoration can be made cheaply and with non-toxic waste materials which could encourage their uptake in developing countries, a new study has found.

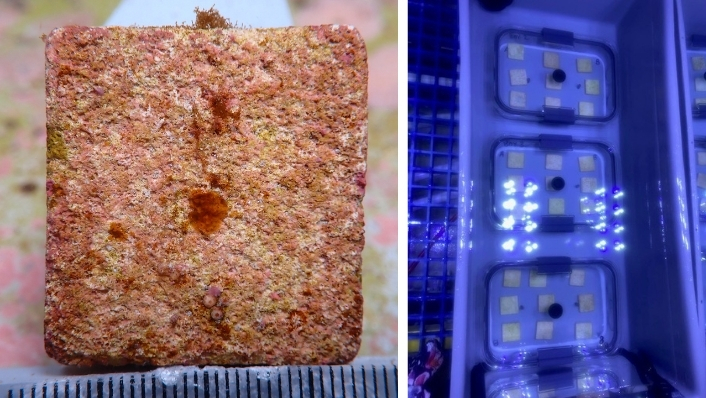

Led by Indonesian marine scientist Dr Widiastuti who was supported by Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) researchers on a recent placement, the study reveals that coral settlement tiles can be made from low-cost clay and common waste materials without impacting the successful settlement of baby corals. The tiles are usually made from ceramics or concrete.

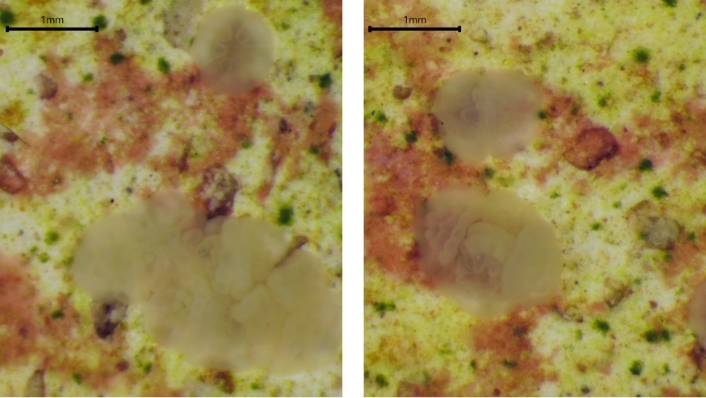

The tiles can be used as part of reef restoration using a method called ‘coral seeding’ where, following spawning in aquaculture facilities, the resulting coral larvae settle onto small tiles. These tiles are subsequently placed onto reefs where the young corals can grow and spread onto the reef surface.

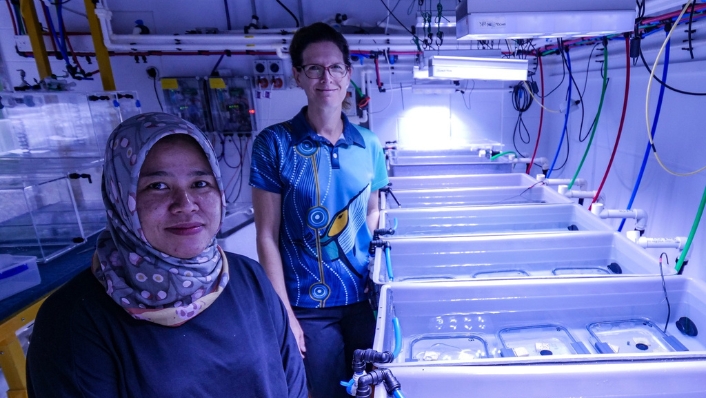

Dr Widiastuti, from the Universitas Udayana in Bali, spent two months at AIMS conducting the experiment and building skills and capacity in coral spawning and aquaculture.

“We found that adding non-toxic waste materials like coconut charcoal, breadcrumbs, or a material known as grog (waste clay from brick making and pottery) to the clay may help corals to settle successfully, because the waste materials combust during tile firing creating crevices that some coral like to settle in,” she explained.

“Adding these materials make the tiles cheaper, and this may also assist with the development of a sustainable local coral aquaculture industry.”

Dr Widiastuti said the most common technique employed in Indonesia to help corals is to detach smaller fragments from a mother coral collected from a reef, grow the fragments in facilities or in special in-water ‘farms’ and outplant them onto coral reefs. This is known as asexual propagation through fragmentation.

“Studies have demonstrated that coral aquaculture methods AIMS is developing - where corals broadcast spawn in aquaculture facilities, and the resulting young corals are settled and distributed onto coral reefs – offer more benefits in terms of genetic diversity for coral communities. The method can also be done at larger scales and long term is less expensive in production costs,” Dr Widiastuti added.

“At AIMS I learned it was essential to understand the spawning window and reproductive potential of the targeted coral species in order to apply this technique. Once I returned to Indonesia, my students and I began collecting data on the spawning window and fecundity of seven Acropora species at reefs around Bali, and we are now ready to share this information and collaborate with marine ornamental companies in our region to increase their sustainability.”

Senior co-author on the paper AIMS’ Dr Cathie Page said the study not only demonstrated how costs could be lowered in restoration, the work supported the development of coral aquaculture and restoration techniques in developing countries.

“This method reduces the need to collect corals from reefs for fragmentation. The finding supports transferring focus to the production of sexually produced corals in aquaculture facilities,” she said.

“Reef restoration and coral exports form an important part of the economy of Indonesia. But the collection of wild corals by exporting industries may be adding to the increasing pressures on coral reefs in these regions from climate change and growing populations.

“We were pleased to work closely with Dr Widiastuti on this project and support the capacity building of scientists in neighbouring Indonesia.”

A paper on this research was published in the journal Coral Reefs and is available here.

Funding for the research was provided by the 2023 Australia Women in Research Fellowship awarded to Dr Widiastuti. AIMS authors were supported by the Australian Coral Reef Resilience Initiative funded by AIMS and BHP.

Co-authors on the paper were also from the National Research and Innovation Agency Indonesia and James Cook University.