The declaration overnight of a global coral bleaching event indicates the increasing pressure climate change is having on reef systems around the world. This is why the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) is prioritising research to underpin scientific solutions to tackle reef resilience.

In confirming the bleaching phenomenon, the United States’ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) stated that significant coral bleaching, caused by ocean heat stress, was documented in both the northern and southern hemispheres of each of the major ocean basins (Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans) from February 2023 to April 2024, affecting communities in at least 53 countries, territories, and local economies.

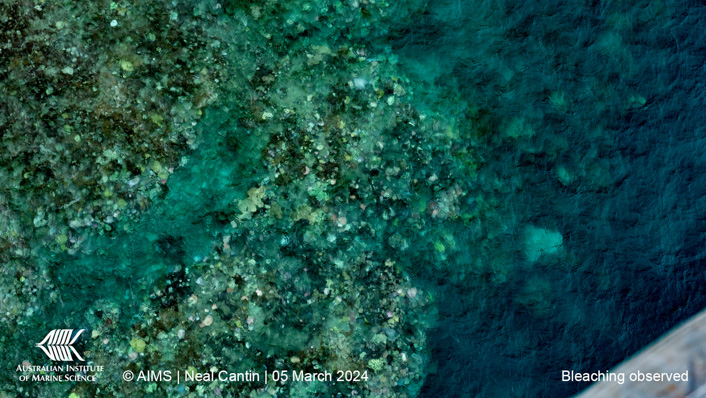

This comes as AIMS, CSIRO, and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority publish the Reef Snapshot later this week which contains further information from aerial bleaching surveys conducted over the Great Barrier Reef in February and March.

AIMS CEO Professor Selina Stead said the global event, the second in the past 10 years, was a reminder of the urgency to use science to mitigate the risk climate change posed to coral reefs and the coastal communities depending on them.

“Climate change is the biggest threat to coral reefs worldwide and this global confirmation illustrates just how extensive its impact has been across the past 12 months,” she said.

“Coral reefs are fundamental to the health of our oceans and the planet. More than half a billion people rely on them across the globe for nutrition, their livelihoods, and socially and culturally.

“Their biodiversity and beauty are unmatched in the ocean, and they provide critical protection for low lying coastal areas from flood and erosion, to name only a couple of external threats. This global event is one which will likely continue to develop for some time.”

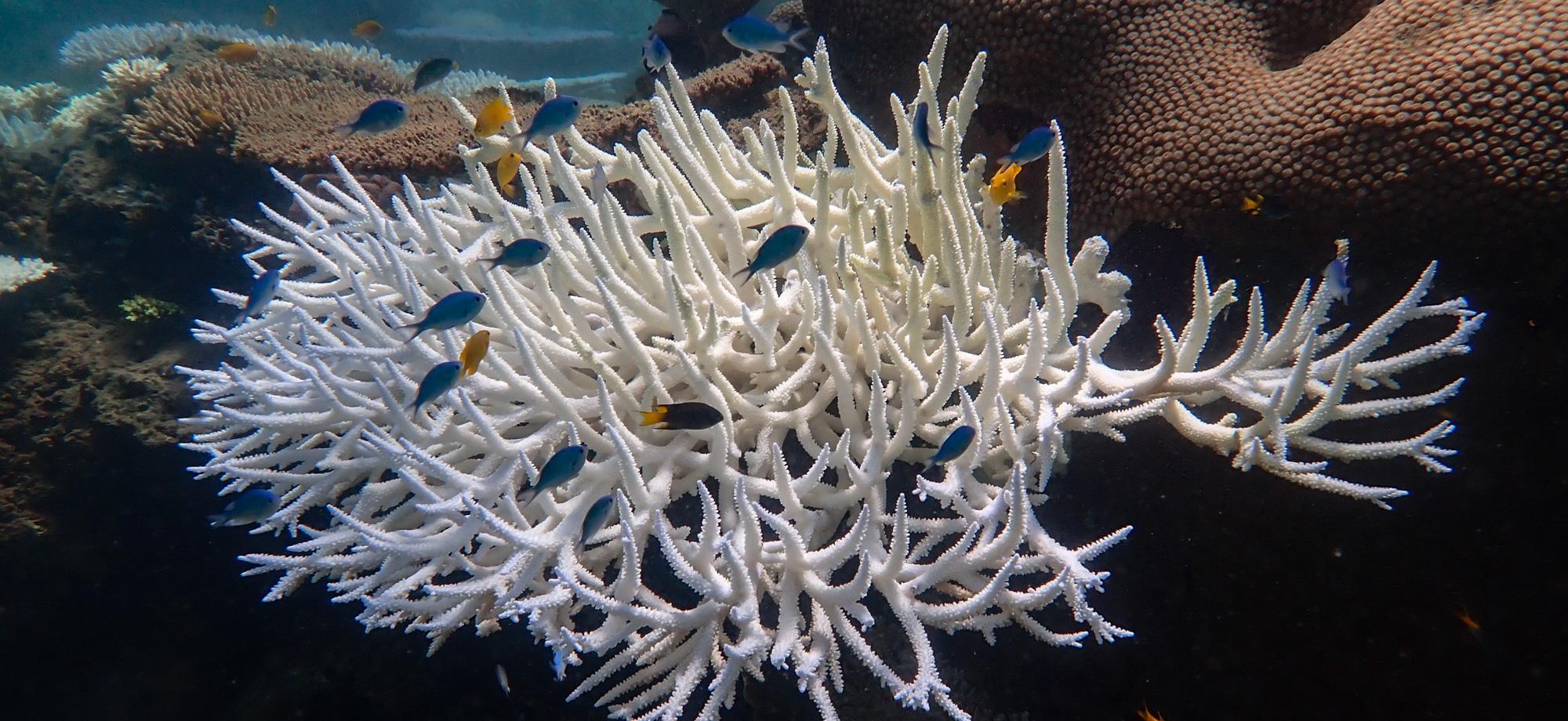

Bleaching is corals’ response to stress, particularly heat stress. Symbiotic microscopic algae living inside the coral’s tissues are expelled, causing the coral to become pale or white. Coral bleaching can cause disease or reduced fertility and can be fatal if the stress is prolonged.

AIMS Manager of International Partnerships and Global Coordinator of the Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network (GCRMN) Dr Britta Schaffelke said the long-term monitoring of reefs around the world was critical to place this event in perspective.

“Coral reefs are naturally dynamic, but more than 40 years of data collected by the GCRMN shows a long-term downward trend of the amount of coral on reefs, driven primarily by marine heatwaves,” she said.

“For example, the first global bleaching event in 1998 is estimated to have caused mortality of 8% of the world’s coral.

“Coral recovered after that event, however data from 2020 showed 14% of the world’s coral reef had died since 2009, and again, most of this was attributed to marine heatwaves caused by climate change.

“We won’t know what the final effect of the current coral bleaching event will be at a global scale until the data is collated from monitoring teams around the world and analysed for the next GCRMN status report, planned for 2025.”

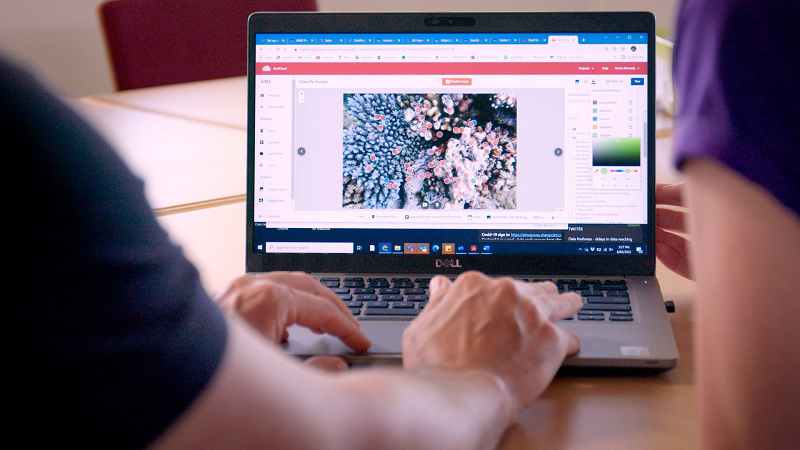

Dr Schaffelke said in recognition of the global challenge to quickly collect up-to-date information about the condition of coral reefs, AIMS was sharing innovations in coral reef monitoring, such as the ReefCloud AI platform, with global practitioners, to help improve understanding and management of the world’s coral reefs.

Professor Stead said AIMS had been preparing for potential widespread coral bleaching in Australia since mid-2023, in addition to its routine long-term monitoring.

“Around 40 of our scientists have been conducting aerial and in-water surveys of the Great Barrier Reef to learn more about the responses of corals to heat stress and to identify naturally heat-tolerant corals,” she said.

“These efforts will help fast track the knowledge needed for more effective management of corals everywhere in an increasingly warming world and inform the research and development of largescale approaches to adaptation and restoration.

“We must continue to innovate and collaborate to develop a toolbox of interventions to help reefs adapt to, and recover from, the effects of climate change.”

In addition, an AIMS science team is currently conducting in-water surveys at oceanic reefs off Australia’s northwest (including Ashmore, Scott and Mermaid Reefs in the eastern Indian Ocean).

Professor Stead said AIMS’ comprehensive, long-term data sets of coral reef condition across Australia provided important insights into how reef ecosystems were responding to a rapidly changing climate.

“We know coral reefs are resilient and can recover, if given enough time,” she said.

“We are focusing on understanding the scientific mechanisms to prioritise actions that can positively impact ocean health. But the increasing frequency and extremity of marine heatwaves, driven by climate change, is testing the tolerance levels of coral reefs.

“That is why it is critical the world works to reduce carbon emissions. It is also important to ensure coral reefs are well managed at local and regional levels, using evidenced-based decisions, so they retain resilience in the face of increasingly challenging times.”

ICRI will be hosting a webinar on Tuesday 14 May 2024 to present and discuss the status of the 4th Global Bleaching Event, and the role of the global coral reef community. Register your interest to attend the webinar here.

Feature image: Martin Reef on 15 March 2024. Photo: Veronique Mocellin

Download images and vision: