A promising mechanism to help improve the thermal resilience of corals at scale has been discovered in the lab by scientists from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) and The University of Melbourne.

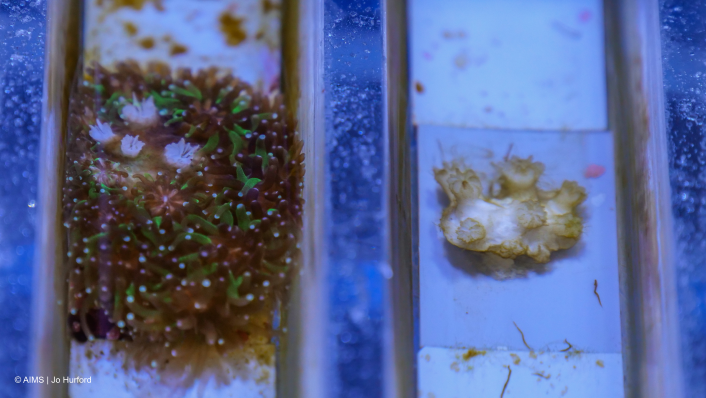

When a coral experiences significant and prolonged heat exposure, it expels the tiny algal cells that live in symbiosis inside the coral and in the process turns white or another pale colour. This is referred to as ‘coral bleaching’. These symbionts are essential to the coral's health, providing them with energy to grow and reproduce. Without their symbiotic algae for an extended period, corals become stressed and may eventually die.

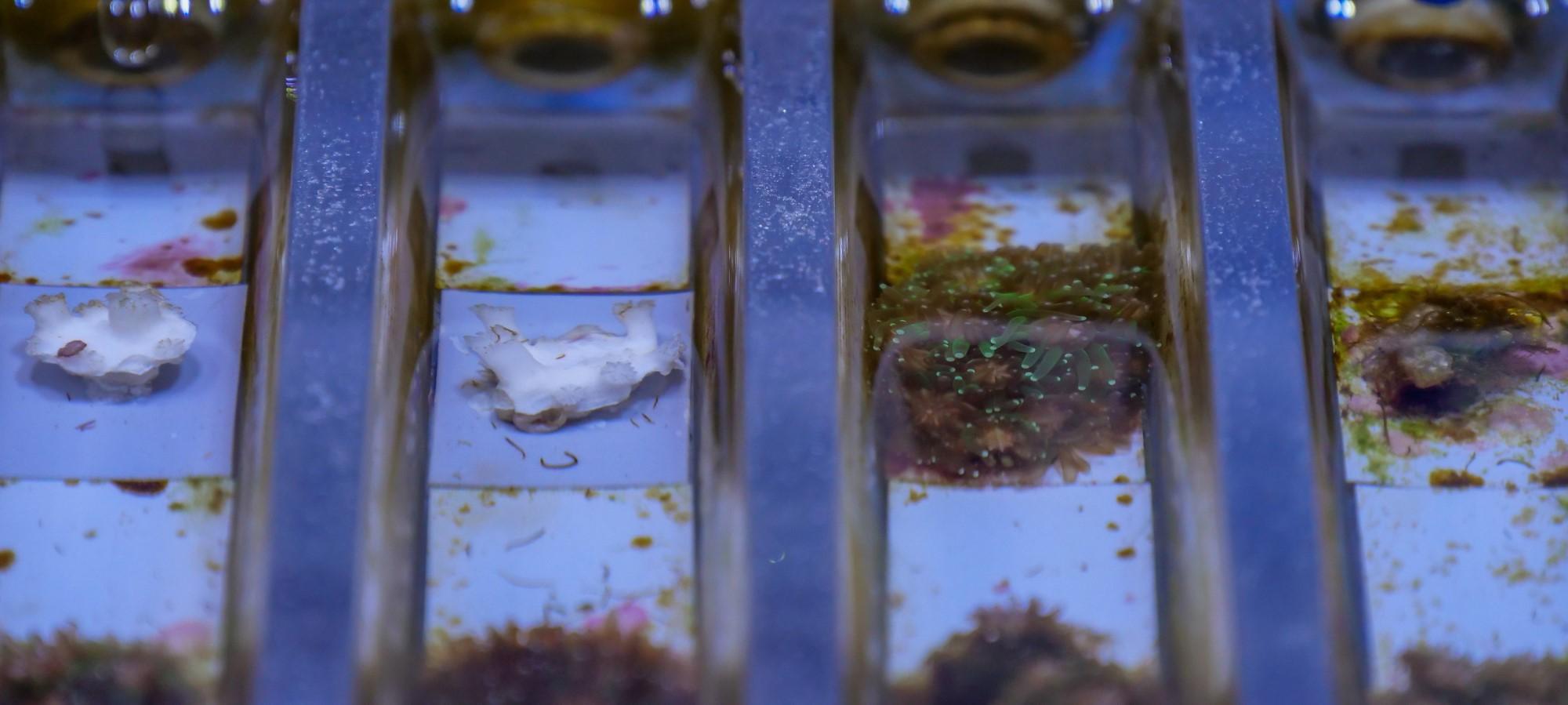

Symbionts are also regularly expelled by their coral hosts when they are not under stress, as one mechanism of regulating their population. Like humans shedding skin cells, this process is not harmful.

The scientists found they can harness the natural process of symbiont expulsion from an adult coral donor to help a bleached coral nearby.

In their latest paper, the researchers led by AIMS and University of Melbourne PhD candidate Bede Johnston, tested whether colonies inoculated with heat-evolved symbionts could donate these symbionts to neighbouring bleached colonies through the water column via natural expulsion.

“We found that expelled symbionts not only remained intact in the water column, but were also taken up by the surrounding bleached corals and able to establish a functional symbiosis with them,” Mr Johnston said.

“Our findings are significant because they provide the first direct evidence of adult-to-adult horizontal transmission of experimentally enhanced symbionts. If heat-evolved symbionts are used in coral reef restoration efforts, this natural mechanism may help the heat-evolved symbionts to spread.

“We propose that deploying healthy adult corals hosting heat-evolved symbionts has the potential to initiate a cycle of symbiont expulsion, uptake by wild corals, and subsequent re-expulsion, ultimately facilitating a reef-scale introduction of heat-evolved symbionts into the water column.”

Senior author on the paper Professor Madeleine van Oppen said the results represented a significant step forward in the use of heat-evolved symbionts as an intervention to enhance the thermal bleaching tolerance of corals.

“With the benefits of heat-evolved symbionts established, it is important to identify the mechanisms that enable their spread on coral reefs,” Professor van Oppen said.

“With coral reefs in Australia and around the world under increasing pressure because of climate change, the development of interventions like these to help corals survive is vital. These results provide important foundational knowledge essential for the scaling up of symbiont-based intervention strategies.”

Further exploration

Mr Johnston said the study is an important first step towards further exploration of this method.

“We have a lot more work to do before understanding whether this would be a viable method of enhancing thermal tolerance over a large scale.

"Next steps for the research would include testing transmission over greater distances and out on the Reef.”

The same research group previously developed a method to boost the heat tolerance of the microalgal symbionts of corals by exposing cultures of these symbionts to elevated temperatures over multiple generations. These symbionts have been found to make their coral hosts more heat tolerant in a lab setting.

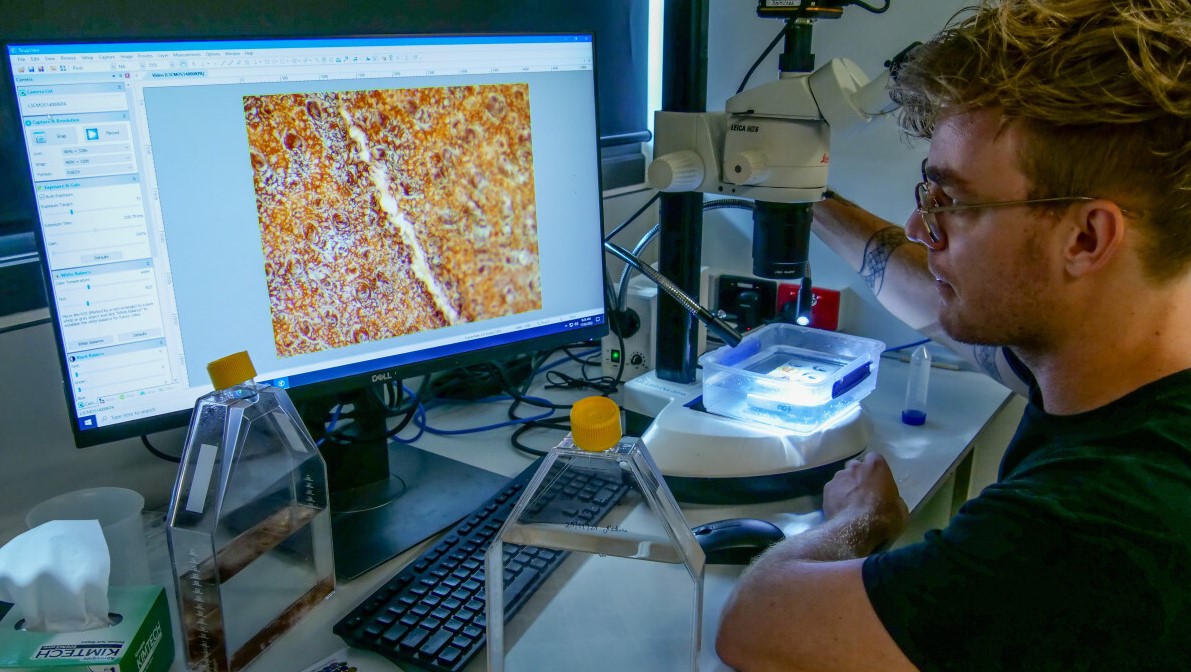

The research was a collaboration between AIMS, The University of Melbourne and Victoria University in New Zealand, with experiments carried out in AIMS’ Symbiont Culture Facility and the National Sea Simulator in Townsville.

The research was funded by the Australian Research Council, Allen Family Philanthropies and the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program (RRAP), which is funded by a partnership between the Australian Government’s Reef Trust and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation.